Feb. 7, 2018

Race against time: Scholars and teachers follow complex paths to revitalize Indigenous languages in Treaty 7 region

Steven Crowchild speaks at the National Vision for Indigenous Language Sustainability workshop.

Darin Flynn

It’s no secret that languages all over the world are disappearing. According to UNESCO, at least 43 per cent of the estimated 6,000 languages spoken in the world are currently endangered. Other reports estimate that one language dies out every 14 days. But what does this mean for us in Alberta? Within the Treaty 7 region, Indigenous languages are facing the threat of extinction, but researchers and community leaders are working hard on preservation.

“For a linguist, the loss of a language is the same as the tragedy a biologist faces when there’s a loss of a species,” explains Betsy Ritter, former interim director of the School of Languages, Linguistics, Literatures and Cultures (SLLLC). “Universities across Canada are beginning to acknowledge that we have an obligation to Indigenous communities to help get back what was taken away from them, and for a linguist, that’s first and foremost language.”

A call to action

Last year, with funding granted from the Faculty of Arts, Ritter and Darin Flynn, associate professor of linguistics, contracted Heather Bliss — a UCalgary alumna and Banting Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Victoria — to explore the important need for language revitalization within Indigenous communities and to recommend actions that should be taken by UCalgary both on- and off-campus. This was a direct response to two of the 94 calls to action put forward by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (10. iv) Protecting the right to Aboriginal languages, including the teaching of Aboriginal languages as credit courses and 16. We call upon post-secondary institutions to create university and college degree and diploma programs in Aboriginal languages.)

Throughout the past year Heather Bliss worked closely with community members on the Tsuut’ina, Stoney Nakoda, and Siksika nations.

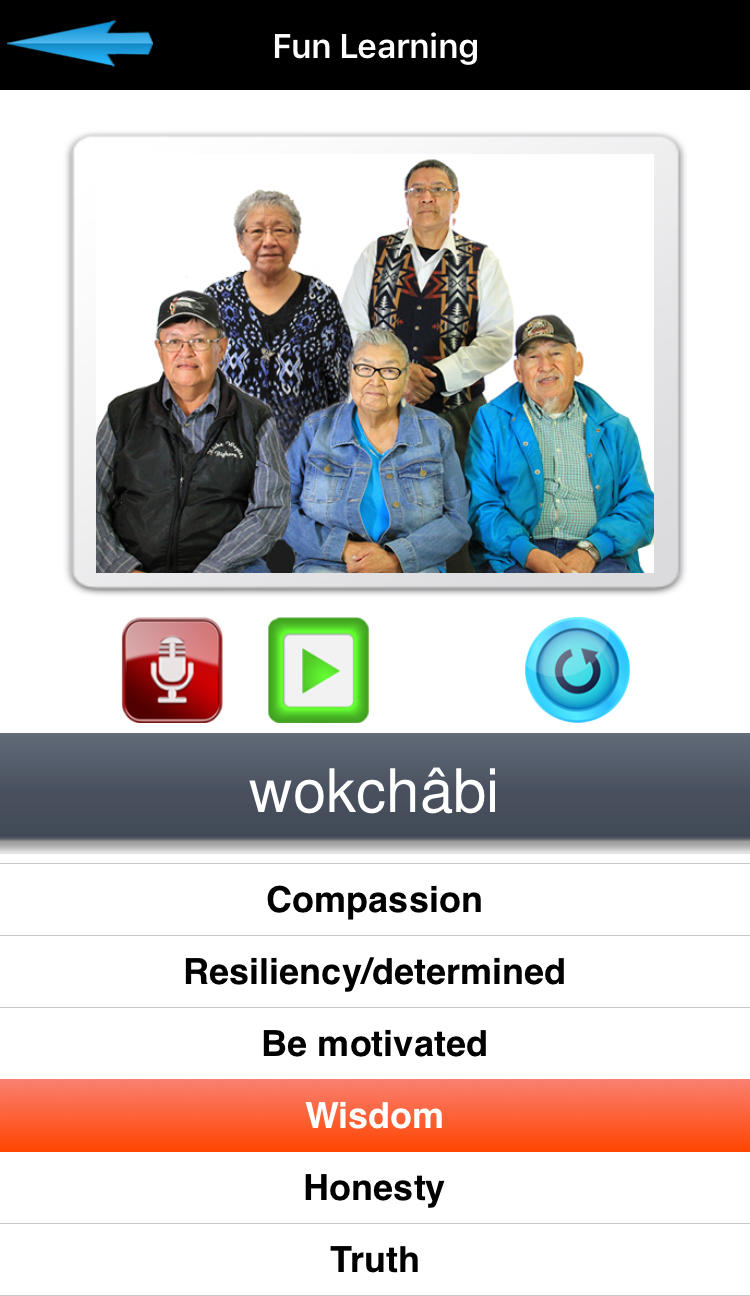

Stoney Nakoda Language App, created by the Stoney Education Authority.

Tsuut’ina

According to Statistics Canada, only 2.7 per cent of the 1,645 people living on the Tsuut’ina reserve southwest of Calgary report the Tsuut’ina language as their mother tongue, making it the most endangered of the languages in the Treaty 7 region. “I would actually say less than two per cent of people are fluent speakers,” says Steven Crowchild, director of the Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute.

Crowchild has been an active teacher on Tsuut’ina for seven years, and has high hopes for language revitalization in the community. Storybooks, animations, sound recordings with elders, resource development, language app for smartphones, and even traditional language drama productions developed by the Tsuut’ina Gunaha Institute have helped to rejuvenate language within all levels of education. These community-led actions are making strides, but it is a slow process that is hard to measure. “It’s kind of a race against time here,” says Crowchild. “Our language is still considered critically endangered, so any time a language keeper passes away it’s a huge loss. People say it’s improving but it’s hard to evaluate where we are right now.”

Crowchild also notes that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to Indigenous language revitalization. “What we would do to revitalize our culture is different from places like Morley, Siksika, Kainai or Pikanii, because of our community dynamics, proximity to the city, our population and different levels of support. But we need to be collaborative. There’s a whole network of people working on things like language apps across North America, and there’s a lot of good sharing that’s happened over the years.”

Stoney Nakoda

West of Calgary on the Stoney Nakoda Nation in Morley, Statistics Canada reports that 56.7 per cent of the of the 3,713 people living on the reserve report Stoney Nakoda as their mother tongue, and 39.2 per cent report Stoney Nakoda as the language spoken most often at home. Comprised of the Chiniki, Bearspaw and Wesley bands, the nation has a higher rate of fluency than Tsuut’ina and Blackfoot, but is experiencing steep declines, especially for younger people.

Duane Mark of the Stoney Education Authority reflects upon the work done in his community to revive the Stoney (Iyethkabi) language, a dialect of Sioux, originating in the central United States. ”The plan is to bring in younger, passionate Stoney language speakers and train them to teach and maintain the Stoney language in our schools.” Three teachers are currently dedicated to teaching language in Morley, one at the elementary level, and one at the junior and senior high levels. Last year, an online pilot program was launched through Morley Community School, which allowed for interactive, distance learning. Canmore Collegiate and Cochrane Bow Valley School have partnered with the program this year, to grow the program to 15 students. The Stoney Education Authority has also recently launched an app, which covers 590 words and features lessons, games and quizzes.

While universities play an important role in training language educators, such as Werklund School of Education student Trent Fox, Mark envisions the future of language revitalization as something that must be deeply steeped in community. “What we really need are visible elders to empower our youth in our schools and enable young trained language ‘warriors’ to teach the language. Stoney language specialist Trent Fox is a language innovator who is able to provide logistical support with language programming extensively. We’re doing well at the moment with our curriculum, but it constantly needs to be reassessed.”

Kainai elder and Blackfoot language teacher Tootsinam Beatrice Bullshields and Heather Bliss.

Phil Wu

Siksika

Looking east, there are approximately 6,000 members of the Siksika Nation, located 100 kms from Calgary. Of the 3,479 people reported as living on reserve, 19.8 per cent report Blackfoot as their mother tongue, and 6.6 per cent report Blackfoot as the language spoken most often at home. This is just one of the three nations within the Blackfoot Confederacy, comprised of the Kainai, Piikani and Siksika, who all use slightly different dialects of Blackfoot.

Noreen Breaker (Ikinomotstaan) is a Siksika elder and UCalgary alumna (BA Canadian Studies, 2003) who has been working with Heather Bliss for more than 10 years on language revitalization efforts in her community. At 72 years old, she is one of the few remaining native Blackfoot speakers, and sees first-hand the difficulties of preservation. “The kids are being taught the language in schools, so they get a head start,” explains Breaker, “but it’s not being spoken at home with their parents, and that is a problem.” As a child, Breaker was one of the lucky few residential school students who was able to go home to her family on weekends where they spoke Blackfoot. Most schools only granted visitation with families for two months out of the year, which quickly erased an entire generation’s connection to their mother tongue.

In order to move forward with hope for new generations, Breaker stresses the importance of documenting and archiving language while there is still time. “It is important for universities to partner with us to develop archives of the language before it’s gone, and develop training programs for teachers to pass on their knowledge”

Bliss’ final report will be presented to Richard Sigurdson, dean of the Faculty of Arts in the coming month, with recommendations for new language training programs as well as a dedicated Indigenous language hub on campus. “I am honoured to be working with incredible language warriors in the Siksika, Stoney Nakoda, and Tsuut’ina communities,” says Bliss. “The words and wisdom they have shared with me give me hope that we can work together in a good way.”

ii’ taa’poh’to’p, the University of Calgary’s Indigenous Strategy, is a commitment to deep evolutionary transformation by reimagining ways of knowing, doing, connecting and being. Walking parallel paths together, ‘in a good way,’ UCalgary will move towards genuine reconciliation and Indigenization.